Chimu Culture Sacrifice

In a small fishing village in Peru, archaeologists have found the remains of 43 children who were brutally killed. The poignant human sacrifice may have been made to halt the cyclical climate pattern El Nino, which was ravaging South America and threatened to destroy the Chimu culture.

A group of children in Huanchaquito, a small fishing village in northern Peru, found something unusual last year as they were playing in the sand outside the local pizzeria: a large collection of old bones. The owner of the pizzeria contacted archaeologist Oscar Gabriel Prieto, who was working at another excavation site nearby at the time, and he and his team decided to look into the discovery.

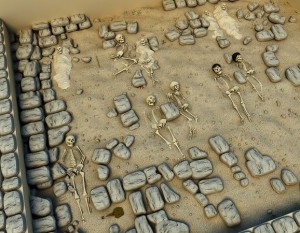

What they found was the site of a mass sacrifice of children; after just one day of work, 20 well-preserved skeletons had been unearthed. And within a few weeks, the archaeologists had found 43 skeletons in total, all of which appeared to have been victims of execution. Each child had received a clean cut through the breastbone, and the chest had been cut open to take out the heart.

The execution method is not sensational in itself — despite its brutality, it has been observed in several ancient cultures, including the Aztec and Maya. But the large number of victims was unusual, as was the presence of 76 slaughtered llamas, animals of great value. It was clear that the sacrifice had been made to placate a very angry god.

The execution method is not sensational in itself — despite its brutality, it has been observed in several ancient cultures, including the Aztec and Maya. But the large number of victims was unusual, as was the presence of 76 slaughtered llamas, animals of great value. It was clear that the sacrifice had been made to placate a very angry god.

Blame it on the rain

The execution took place 600 to 800 years ago, when the Chimu culture ruled the area. The Chimu were farmers and fishermen, as well as able merchants who built a wealthy empire.

But signs indicate that a dark shadow loomed over the empire — one that well may have had something to do with the weather. Deposits in the soil show that it had been raining heavily for a long time just before the sacrifice was made. And studies have shown that El Nino, a cyclical climate pattern marked by heavy rains, was having an impact on the north coast of Peru at the time. El Nino’s torrential downpours can cause landslides and flooding, and the archaeologists think that the children and llamas may have been sacrificed in large numbers to appease the gods and stop the rain.

But signs indicate that a dark shadow loomed over the empire — one that well may have had something to do with the weather. Deposits in the soil show that it had been raining heavily for a long time just before the sacrifice was made. And studies have shown that El Nino, a cyclical climate pattern marked by heavy rains, was having an impact on the north coast of Peru at the time. El Nino’s torrential downpours can cause landslides and flooding, and the archaeologists think that the children and llamas may have been sacrificed in large numbers to appease the gods and stop the rain.

Food supply at risk

A majority of the Chimu were farmers and thus depended on stable weather, which the region enjoyed most of the time. The dry desert areas along the coasts of Peru were probably not well suited for crops, but the inhabitants had nonetheless managed to develop a flourishing agriculture.

Around the Chimu capital of Chan Chan, archaeologists have previously found evidence of two ingenious cultivation techniques that can make crops grow in an otherwise bone-dry desert.

One method was efficient irrigation, in which the Chimu diverted vast amounts of water from a nearby river and into their fields. The canals they used were up to 18 miles long and branched off into smaller canals, forming a network of irrigation channels around a cleverly designed series of fields. The canals had sluices that were precisely inclined to allow the farmers to control exactly how much water each location received, making optimal use of the water supply and avoiding waste.

The Chimus other clever innovation was sunken fields. They removed the soil down to the water table and planted their crops just above the water supply. Around the capital of Chan Chan, the fields were located 16 to 33 feet below the surface. This required the removal of a lot of soil, but once a field had been established and irrigated, it yielded a good harvest, providing the inhabitants of the desert city a varied and nourishing diet.

Then El Nino came along and everything went wrong, as fields and canals were inundated with rainwater and mud.

Seeking the gods’ mercy

It fell to the people to make the ultimate sacrifice. By slaughtering their children to appease the gods, they were ensuring that the rest of the population had a future. This undoubtedly granted the victims’ families special status. Children were precious in Chimu society, and the sacrifice of as many as 43 is astonishing.

It fell to the people to make the ultimate sacrifice. By slaughtering their children to appease the gods, they were ensuring that the rest of the population had a future. This undoubtedly granted the victims’ families special status. Children were precious in Chimu society, and the sacrifice of as many as 43 is astonishing.

The children were not taken to Chan Chan’s usual closed places of sacrifice, but down to the ocean, which is where the archaeologists found them. They had been placed in small groups, most facing north or west. Prieto thinks that this makes sense, given that they would thus be facing the ocean and the north, where the warm currents that caused the flooding came from. The victims were not accompanied by tomb presents or other items indicating a separate burial. They were left where they fell to the ground.

The 76 llamas were also of great value. They were a central element of the Chimu culture and used for all kinds of transport, as well as for their meat and fur. All of the animals were young and strong, so the loss must have been a significant economic burden. Their role in the sacrifice is not definitively known, but they may have been intended to take the children to the kingdom of the gods.

Prieto will continue his studies in conjunction with a team of experts from a variety of fields. They hope that further analysis of the children’s bones, hair and teeth will reveal more about them: their age, gender, family relations and, most poignantly, whether they were doped prior to the brutal sacrifice.

THE RICH CHIMU CULTURE

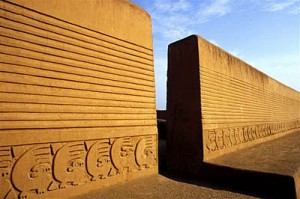

The sacrificed children were members of the Chimu culture, which ruled large parts of Peru until the Incas arrived in 1470. The capital, Chan Chan, was the center of the empire and the largest city in South America at the time. In its heyday, Chan Chan covered an area of about 11 square miles and boasted around 30,000 inhabitants.

The sacrificed children were members of the Chimu culture, which ruled large parts of Peru until the Incas arrived in 1470. The capital, Chan Chan, was the center of the empire and the largest city in South America at the time. In its heyday, Chan Chan covered an area of about 11 square miles and boasted around 30,000 inhabitants.

The Chimu princes ruled several other local tribes, who were forced to pay tribute through labor. This enabled Chimu royalty to become very wealthy, with each prince building his own residence in a citadel situated within the capital. When the prince died, he was buried with his wives, concubines, llamas and large amounts of gold and silver, and the citadel was closed.

BAD WEATHER, MORE VICTIMS

Archaeologists have found other human sacrifices in Peru that can be linked to El Nino and the torrential rain it brings.

In the small town of Huanchaco in 1968, archaeologist Christopher Donnan found 17 children and 20 llamas that had all been sacrificed. The town is located near Huanchaquito, so Oscar Gabriel Prieto and Donnan think that the two finds are related. In the Moche Valley, archaeologists have excavated the ceremonial site of Huaca de la Luna, which harbors a major complex of buildings built by the

Moche Indians, who ruled northern Peru prior to the Chimu culture. In 1996, archaeologists found three sacrificed children and many warriors there. The layers that they are buried in show clear signs of heavy rains. Climate studies have revealed that a particularly severe El Nino occurred in the mid-500s, which probably was a significant contributing factor to the demise of the Moche culture.