Ancient Olympics Facts

The modern Olympic Games may certainly look very different to what took place hundreds of years ago, but the underlying ethos hasn’t changed in millennia!

The ancient heroic code was, as the epic poet Homer put it, ‘to strive always to be the best, superior to others’; hence the modern Olympic motto, ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger‘. The Ancient Greek world consisted of about 1,500 economically independent city-states, dotted around the coastlines of the Mediterranean and Black Seas, and these states were often at war with one another. Nevertheless, they all thought of themselves as Greeks, and they invented sport, and international festivals such as the Olympic Games, as opportunities to test themselves against their peers without shedding blood – or not too much of it, anyway! The games were even protected by a sacred truce so that competitors and spectators could travel in safety. So, every four years, thousands made their way to the Peloponnese, the southern peninsula of Greece, where Olympia was situated. Like today, athletes competed for a combination of individual and national glory. The origins of the games are lost in the mists of time: like other games in Ancient Greece, the Olympic festival probably began in celebration of the death of a local hero -perhaps Pelops himself, after whom the Peloponnese is named (‘the island of Pelops’). But the Greeks themselves said that the games began in 776 BCE, and took that year as the start of the first Olympiad.

The year 2012 begins the 30th Olympiad of the modern era (since the competition restarted in 1896), but – technically – it begins the 697th Olympiad. The 2012 Olympics recently took place in London, with the 2016 event being held in Rio de Janeiro.

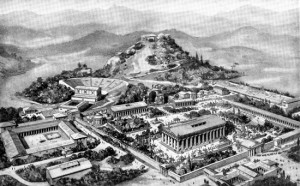

Ancient Olympia

The sacred enclosure and its landmarks!

The Olympic Games, which were held from 776 BCE to 393 CE, were first and foremost a five-day religious festival dedicated to the glory of Zeus. Within the sacred enclosure – the Altis – were the spaces employed for the athletic competitions and the god’s worship, as well as for the ceremonies that took place during the festival. By the Classical period numerous buildings populated the area, and the stadium and hippodrome (not shown below) were enhanced. Most of what we see today has been excavated, in a joint venture between the Greek Archaeological Service and the German Archaeological Institute, since 1936.

The Olympic Games, which were held from 776 BCE to 393 CE, were first and foremost a five-day religious festival dedicated to the glory of Zeus. Within the sacred enclosure – the Altis – were the spaces employed for the athletic competitions and the god’s worship, as well as for the ceremonies that took place during the festival. By the Classical period numerous buildings populated the area, and the stadium and hippodrome (not shown below) were enhanced. Most of what we see today has been excavated, in a joint venture between the Greek Archaeological Service and the German Archaeological Institute, since 1936.

Facts about Olympics

Politics and sport – The unhappy involvement of politics is not only a modern phenomenon. The ancient organizers too sometimes tarnished the Olympic spirit by excluding rival city-states.

Politics and sport – The unhappy involvement of politics is not only a modern phenomenon. The ancient organizers too sometimes tarnished the Olympic spirit by excluding rival city-states.

The marathon – There was no marathon race in the ancient Games – the story of Pheidippides’ run from the Battle of Marathon to Athens in 490 BCE is only a legend.

Winning women? – Women were not allowed to participate in the ancient games, but could be registered as victors – by putting up the money for a winning chariot team.

War games – The Summer Olympics were cancelled due to war in 1916, 1940 and 1944, and the same happened in ancient times too. However, these still count for dating reasons.

Pierre de Coubertin – The modern Olympics were the brainchild of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who felt he was resurrecting the bygone ideal of ‘a sound mind in a sound body’.

Origins of the Olympic Games A-Z

Altis – This is the enclosure, sacred to Zeus, where the Olympic festival took place. For the Olympic Games were a religious festival, not just a sporting event, and the central event of the five-day games was a hecatomb – the enormously lavish sacrifice of 100 oxen at Zeus’s altar.

Altis – This is the enclosure, sacred to Zeus, where the Olympic festival took place. For the Olympic Games were a religious festival, not just a sporting event, and the central event of the five-day games was a hecatomb – the enormously lavish sacrifice of 100 oxen at Zeus’s altar.

Boxing – Although similar to modern-day boxing, the rules were not quite the same, above all because there were no rounds. Competitors just slugged it out, with their hands wrapped in strips of leather, in a ring formed of spectators, until – maybe hours later – one man was knocked out or collapsed.

Chariot-racing – was extremely dangerous, and the wealthy owners trained slaves for all the equestrian events. The two events involving chariots were held in the hippodrome, which was about 600 metres (1,970 feet) long, and wide enough to allow up to 40 chariots to race at one time.

Diet – Ancient athletes recognized the importance of eating special foods for energy and muscle development; they even argued about whether one should abstain from sex while training. An athlete’s diet was richer in meat than the normal Greek diet.

Events – The only events were those considered suitable training for warfare: boxing, wrestling, pankration (a brutal form of ancient martial art with almost no rules), four running races, the pentathlon, chariot-racing and several equestrian events.

Flame – A conspicuous aspect of the modern Olympics is the ceremonial lighting at Olympia of the Olympic flame. This is said to commemorate Prometheus’s mythical gift of fire to mankind, but in fact it had no ancient counterpart, and was first introduced for the 1928 Olympics held in Amsterdam.

Flame – A conspicuous aspect of the modern Olympics is the ceremonial lighting at Olympia of the Olympic flame. This is said to commemorate Prometheus’s mythical gift of fire to mankind, but in fact it had no ancient counterpart, and was first introduced for the 1928 Olympics held in Amsterdam.

Gymnasium – The gymnasium was simply a practice area. The actual events were held outdoors, in the blazing heat of a southern Greek summer, but the Greeks were sensible enough to want to practise indoors. The Olympic gymnasium provided the athletes with all the facilities they needed for both training and relaxation.

Heracles – The ultimate strongman, Heracles (who was known as Hercules to the Romans), is credited in one story with founding the Olympic Games. He filled his lungs and sprinted until he needed to draw breath again, and that spot marked the end of the stadium. Apparently, he could hold his breath for approximately 200 metres (660 feet).

Inscriptions – The Altis gleamed with statues in bronze and marble of famous athletes or dignitaries. But, positioned so that athletes would see them as they entered the stadium, there was also a terrace of statues inscribed with the names of cheats, and put up at their expense as a punishment.

Jugglers – The ancient Olympics were not just an occasion for sport. In a carnival-like atmosphere, poets and orators declaimed, peddlers and prostitutes hawked their wares, and jugglers and other kinds of performers offered entertainment. Spectators mingled in their thousands with contestants and their trainers, slaves and priests, alongside representatives from every walk of life.

Kallipateira – Having no surviving male relatives to train her son, Kallipateira of Rhodes trained him up herself, and defied the strict ban on female presence at the Olympics by disguising herself as a man. Her deception was discovered, however, when she leapt for joy at her son’s success and exposed herself.

Kallipateira – Having no surviving male relatives to train her son, Kallipateira of Rhodes trained him up herself, and defied the strict ban on female presence at the Olympics by disguising herself as a man. Her deception was discovered, however, when she leapt for joy at her son’s success and exposed herself.

Leni Riefenstahl – For the Berlin Olympics of 1936 Adolf Hitler had the filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl carve the five interlocked Olympic rings onto a stone, to suggest that this was an ancient symbol, but in fact it was invented in 1913, to represent the five main regions of the world.

Milo – Milo of Croton (a Greek city in southern Italy) was perhaps the most famous athlete of the ancient world. He was a wrestler, and he achieved the astonishing feat of winning in six successive Olympics, once as a boy and five times as an adult.

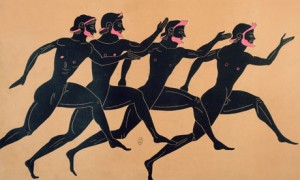

Nudity – For all the track and field events, the male contestants were nude. Penises were tied back against the body with a leather string to minimise discomfort. There were few female spectators, and homoerotic admiration was encouraged by the gratuitous practice of rubbing athletes’ bodies with olive oil until they gleamed.

Oath – The spirit of the ancient Olympic oath was exactly the same as its modern counterpart – except that nowadays the oath is not administered over a slice of raw boar meat. Essentially, the athletes swore to play fair, and the judges to judge fairly and not to divulge information about any of the contestants.

Oath – The spirit of the ancient Olympic oath was exactly the same as its modern counterpart – except that nowadays the oath is not administered over a slice of raw boar meat. Essentially, the athletes swore to play fair, and the judges to judge fairly and not to divulge information about any of the contestants.

Pentathlon – The pentathlon consisted first of the three events that were peculiar to it: discus, javelin and long jump. If there was no clear champion after the first three events, the contestants were narrowed down by a sprint; if there was still no clear winner, then it was decided by a wrestling match.

Quadrennium – The Olympic Games were held, as now, every four years. The other most famous games – at Delphi, Nemea and Corinth – were four-yearly or two-yearly festivals, and were spaced so as not to clash with the Olympics, and so that athletes could attend a major festival in any given year.

Ribbons – The prizes at the Olympic Games in Ancient Greece were no more than ribbons – bands, intertwined with sprigs of wild olive, to wreathe the heads of the victors. The winner gained enormous prestige, and that was all – though that was sometimes enough to bring him fame and fortune back home, perhaps in the political arena.

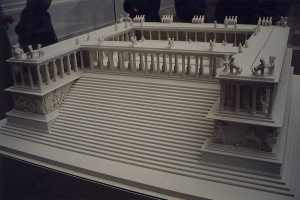

Stadium – The sandpit was the venue for wrestling, the hippodrome for equestrian events, and the rest were held in the stadium, whose grassy banks could seat 40,000 spectators. The four footraces were: one- and two-stade sprints, a 20-stade slog and a two-stade race run in armour.

Stadium – The sandpit was the venue for wrestling, the hippodrome for equestrian events, and the rest were held in the stadium, whose grassy banks could seat 40,000 spectators. The four footraces were: one- and two-stade sprints, a 20-stade slog and a two-stade race run in armour.

Training – The Ancient Greek lifestyle guaranteed a basic level of fitness, but athletes also practiced their specific events and cross-trained through dancing, for instance. All contestants also trained for the month preceding the games in the Olympic gymnasium.

Underhand dealings – Cheating was rare: the few events did not readily lend themselves to it, though officials could potentially be bribed. Despite having a range o medications, the use of performance-enhancing drugs doesn’t seem to have been an issue.

Victory – The Greeks were not sportsmen in our sense: victory was all, and coming second counted as defeat. Nor were they interested in world records: accurate measurement was difficult, so the focus was on beating your rivals in the immediate event.

Women – Except for a single priestess and unmarried girls, women were not allowed into the ancient Olympics. But an all-female festival was organized at Olympia, just before or after the male games. Sacred to Hera, the goddess wife of Zeus, these games consisted of no more than a few footraces.

Excellence – Competition was a major part of an aristocrat’s life – hence the importance of the Olympic Games. Only one’s peers counted: Alexander the Great quipped, when asked if he’d enter the sprint, “Only if my opponents are also kings.”

Excellence – Competition was a major part of an aristocrat’s life – hence the importance of the Olympic Games. Only one’s peers counted: Alexander the Great quipped, when asked if he’d enter the sprint, “Only if my opponents are also kings.”

Youth – Olympic events fell into three age categories: boys (aged 12-15), youths (16-18) and men (over 18). Success at Olympia could radically change a boy’s life. He seemed to be destined for greatness, and back home he would be groomed to play a major part in his city’s political life.

Zeus – Pheidias’s 13-metre (43-foot)-high gold-and-ivory statue of the enthroned god, housed in his temple at Olympia, was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Zeus’s altar, north of the temple, supposedly marked the spot where he struck the site with his thunderbolt, claiming it as sacred to his worship.