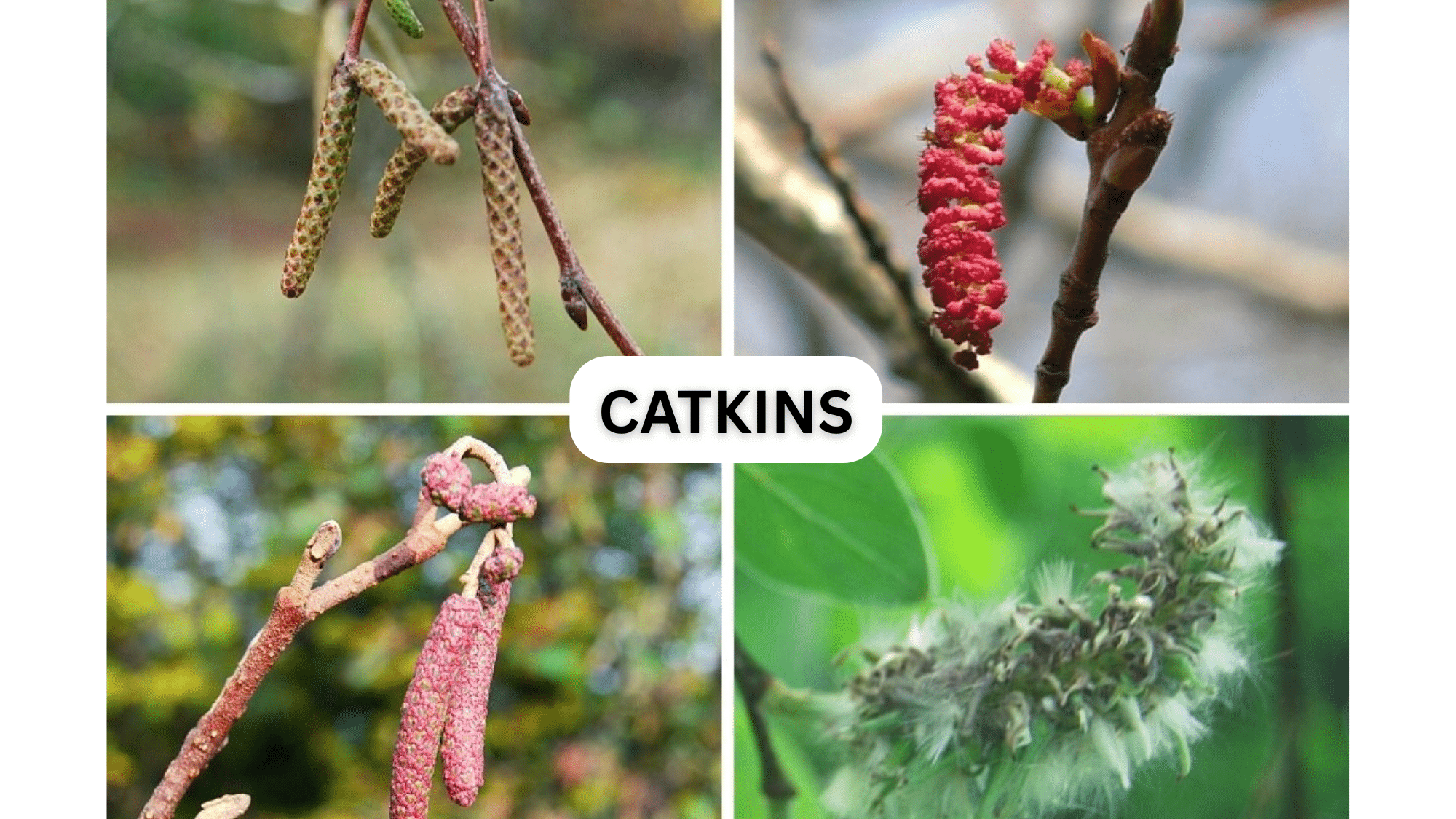

Have you ever noticed those fuzzy, hanging structures on trees in early spring?

Those are catkins, one of nature’s most beautiful yet often overlooked flowering displays.

These distinctive structures play a crucial role in tree reproduction and mark the beginning of the growing season for many common trees.

Let’s know the world of catkins and learn why they’re worth your attention.

About Catkins

Catkins are slim, hanging flower clusters that resemble tassels or a cat’s tail, hence the name, from the Dutch word katteken, meaning kitten.

Unlike colorful flowers that attract insects, catkins are built for wind pollination.

Most catkins are either male or female. Male catkins are longer and more visible, releasing large amounts of lightweight pollen.

Female catkins are smaller and develop into seed-bearing structures once pollinated. Some trees have both types on the same tree, while others have them on separate trees.

With no petals, scent, or nectar, catkins rely entirely on the wind. This simple and efficient design allows trees to reproduce early in the spring, before many insects are present.

When Do Catkins Appear

Timing is everything in the world of catkins. Most appear in early to mid-spring, though the exact timing varies by species and climate:

- Early Bloomers (February-March): Hazel, alder, and some willows produce some of the earliest catkins, sometimes even developing during winter and opening at the first signs of spring.

- Mid-Spring (March-April): Birch, poplar, and most willow species display their catkins during this period, coinciding with leaf emergence in many cases.

- Later Spring (April-May): Oak, beech, and hornbeam produce their catkins slightly later, often as their leaves are developing.

Many trees actually form their catkin buds during the previous growing season, allowing them to burst into bloom rapidly when spring arrives.

This gives them a reproductive head start before leaves fully emerge and potentially block wind currents needed for pollination.

List of Trees Having Catkins

Here’s a list of common trees you might come across with these distinctive hanging structures:

1. Willow (Salix spp.)

Willows are fast-growing trees often found near water. They produce long, drooping catkins in early spring, with male and female flowers usually on separate trees.

Fun Facts:

- Willow bark was once used to make aspirin.

- Their roots help prevent soil erosion.

- Willows symbolize mourning and healing in many cultures.

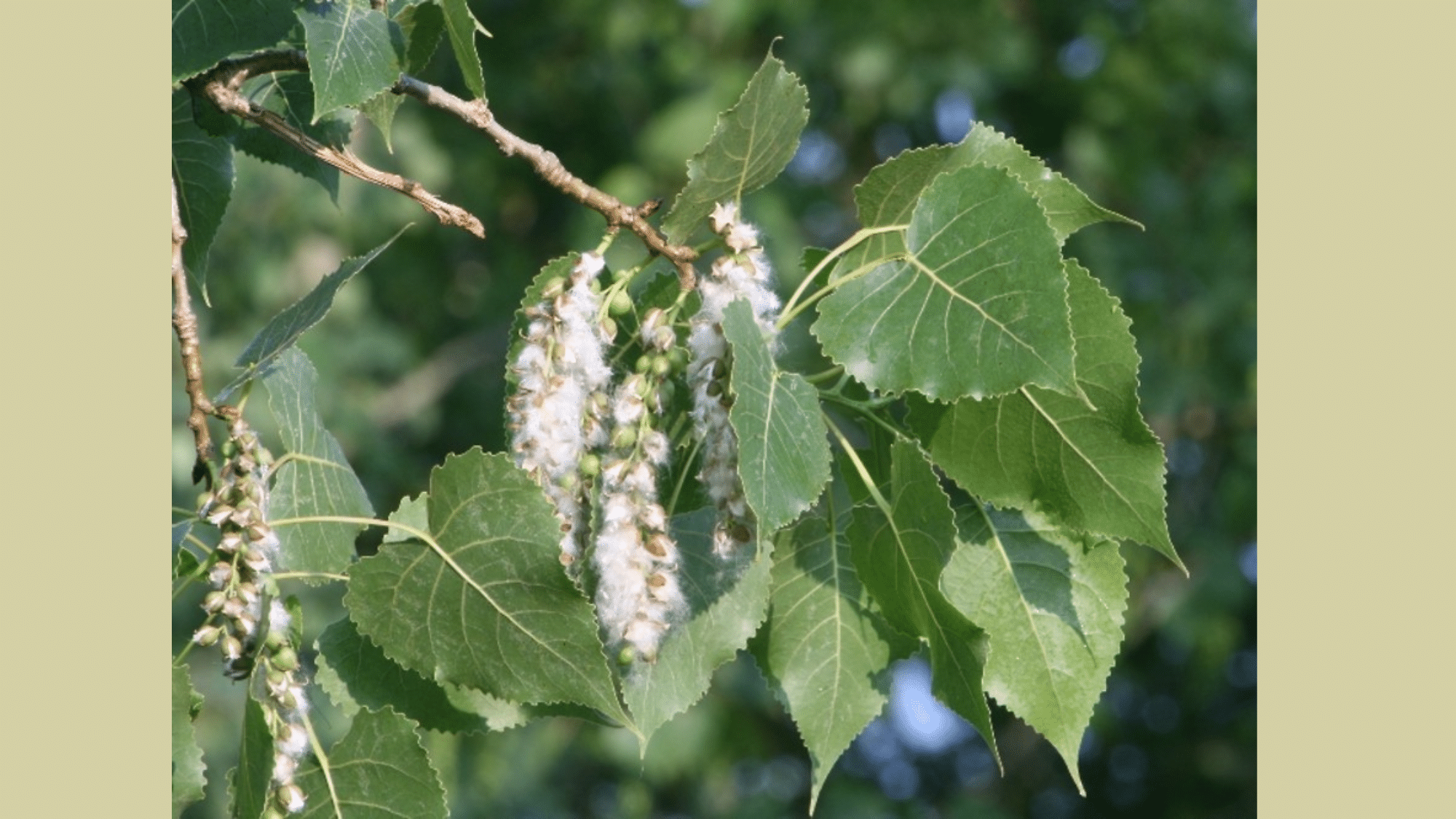

2. Birch (Betula spp.)

Birch trees have papery bark and slender trunks. They produce both male and female catkins on the same tree, with male catkins forming in the fall and blooming in spring.

Fun Facts:

- Birch bark is waterproof and was used for canoes.

- It’s one of the first trees to grow after forest fires.

- The sap is edible and sometimes used to make syrup.

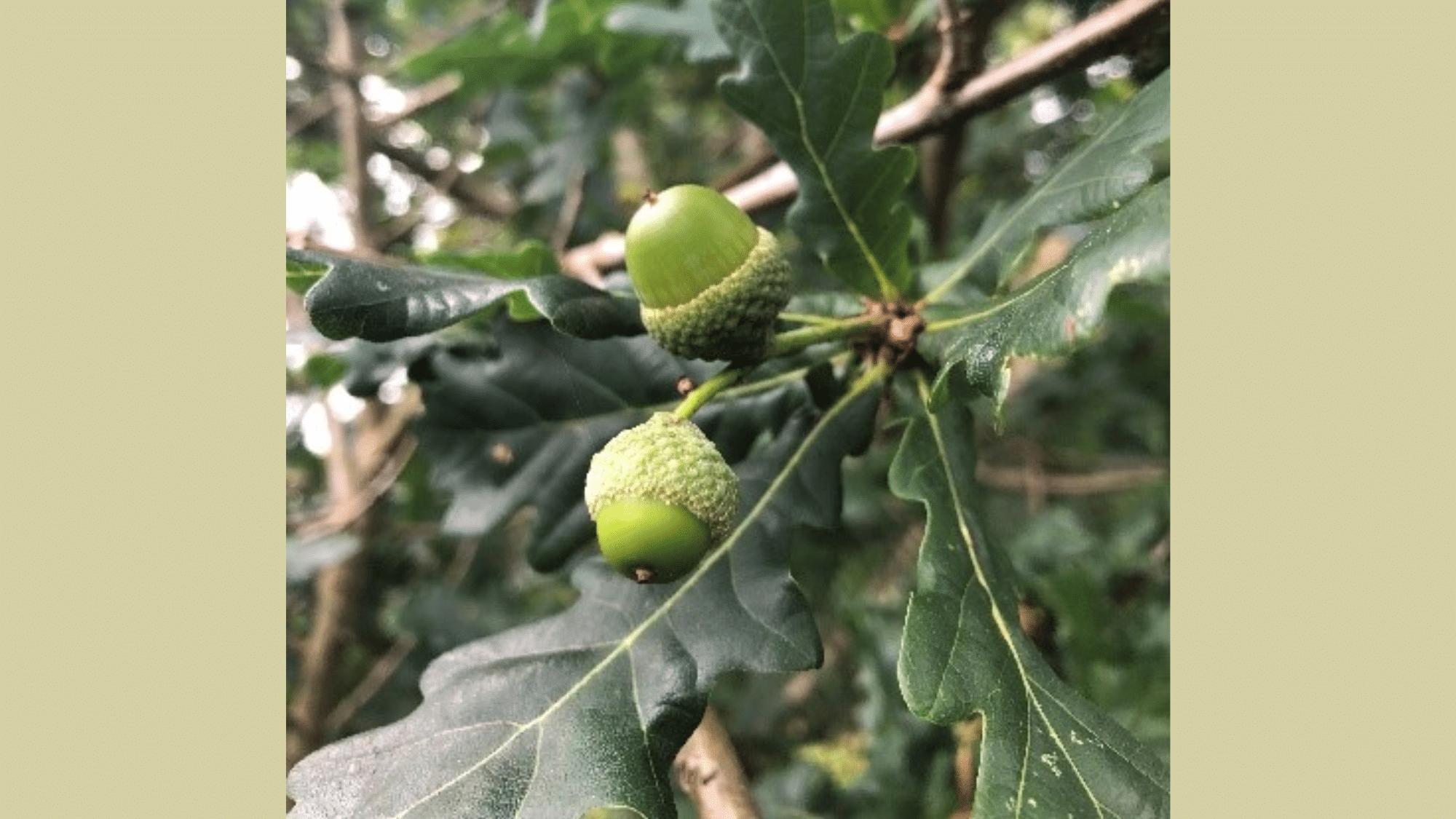

3. Oak (Quercus spp.)

Oaks are strong, long-living trees. Their male catkins dangle and release pollen in spring, while female flowers are tiny and develop into acorns.

Fun Facts:

- Some oaks live over 1,000 years.

- Acorns were once ground into flour.

- Oaks support more wildlife than any other tree in many regions.

4. Poplar (Populus spp.)

Poplars are tall, fast-growing trees often found in open areas. They produce long catkins, with male and female flowers on separate trees.

Fun Facts:

- Poplars grow up to 5–6 feet per year.

- Their wood is used in matches and paper.

- Poplar fluff (from seeds) can look like summer snow.

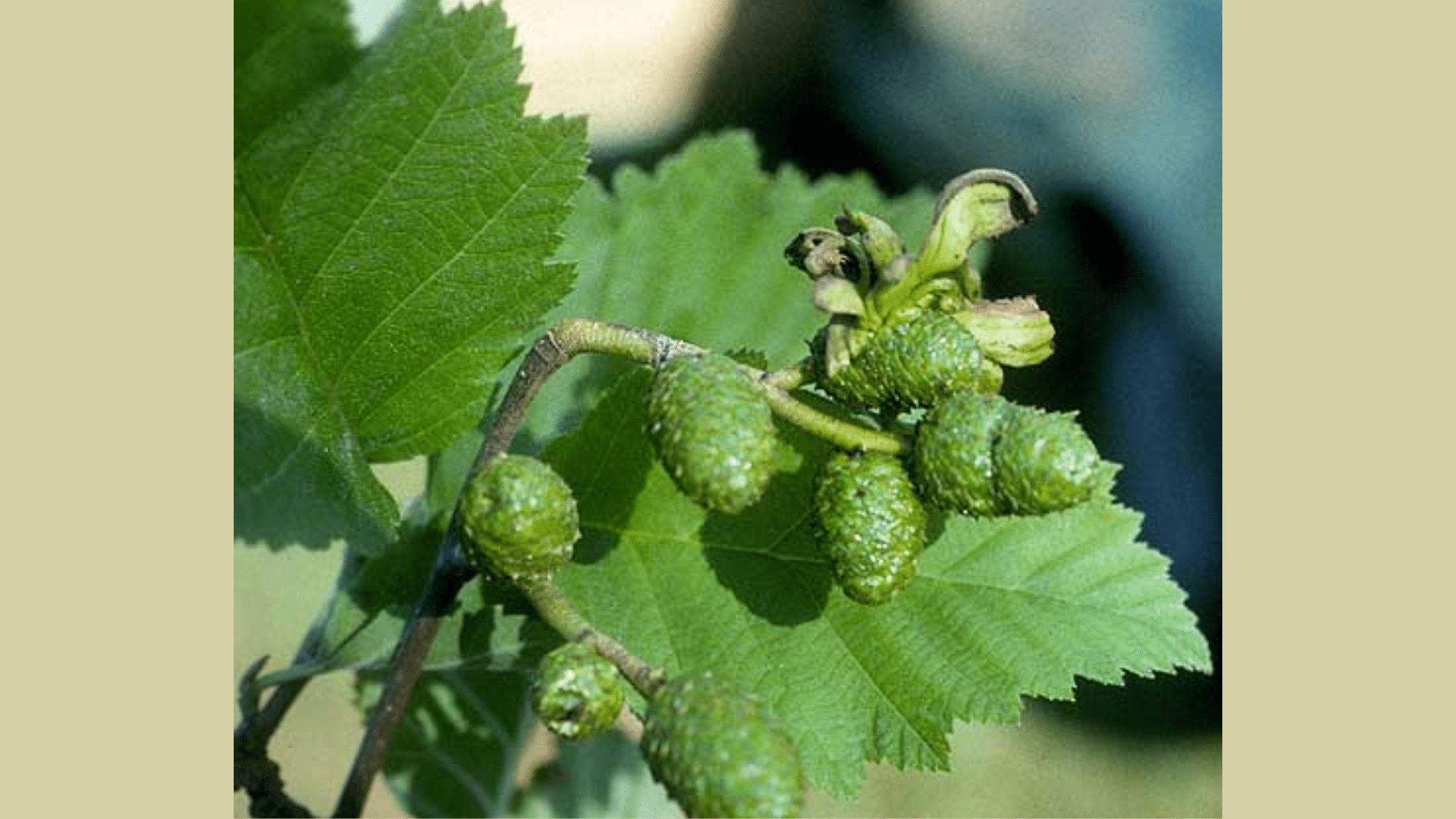

5. Alder (Alnus spp.)

Alders grow near rivers and moist soils. They produce both male and female catkins, with male catkins being more noticeable and longer.

Fun Facts:

- Alder roots improve soil by fixing nitrogen.

- The wood doesn’t rot in water, used in Venice’s foundations.

- Their cones stay on the tree even in winter.

6. Hazel (Corylus spp.)

Hazel trees are small, bushy trees or large shrubs. They produce long, yellow male catkins in late winter to early spring and tiny red female flowers on the same plant.

Fun Facts:

- Hazelnuts are edible and highly nutritious.

- Hazel twigs were used in ancient divination (dowsing).

- They attract early pollinators like bees.

7. Beech (Fagus spp.)

Beech trees are large, shade-loving trees with smooth gray bark. They produce both male catkins and small female flowers in the spring, often on the same tree.

Fun Facts:

- Beech nuts (called beechnuts) are edible for wildlife and humans.

- Their dense canopies shade out the undergrowth.

- Beech wood is popular for furniture and flooring.

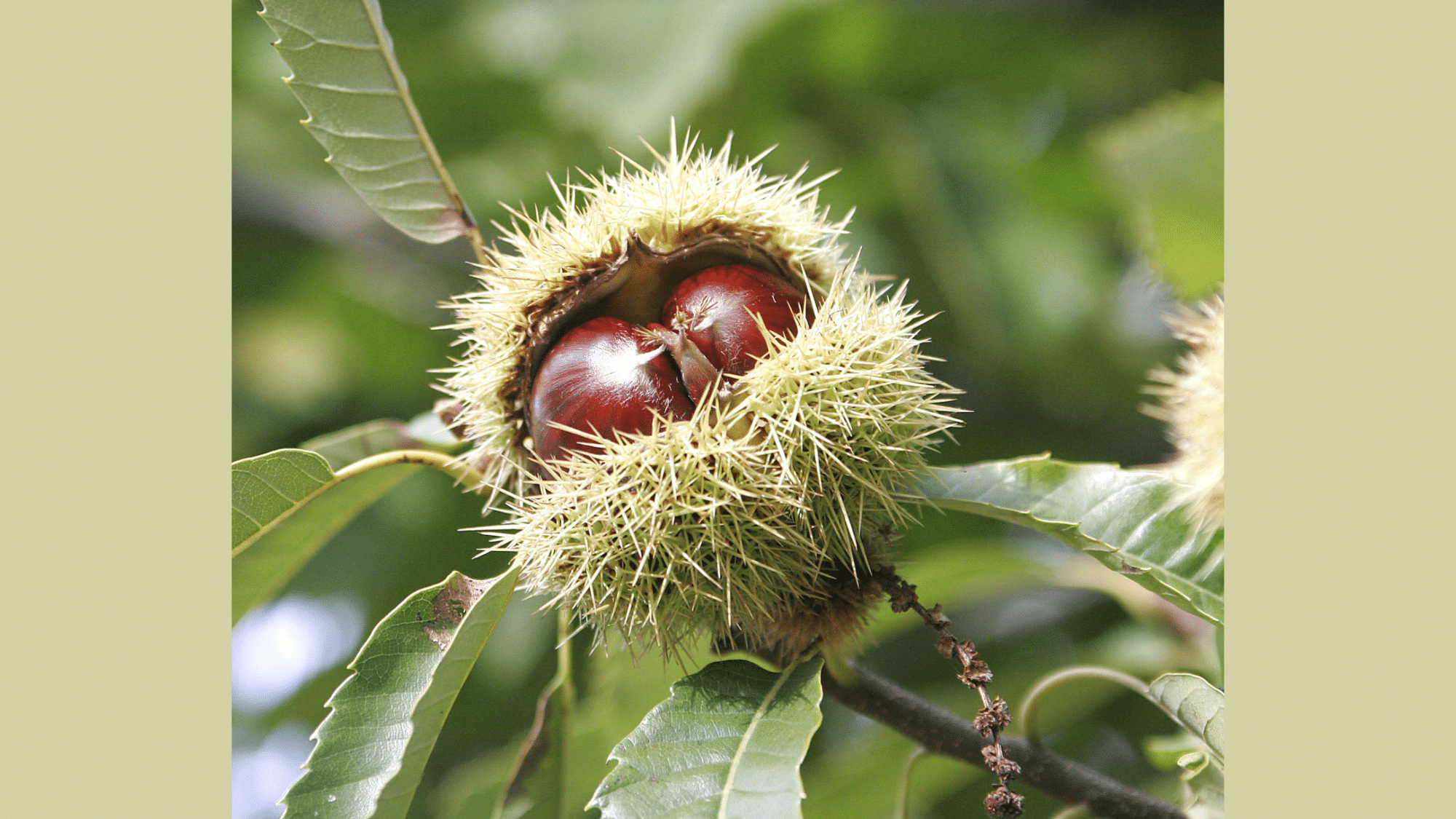

8. Chestnut (Castanea spp.)

Chestnut trees produce long, showy male catkins and less visible female flowers. These trees are known for their edible nuts and wide-spreading canopies.

Fun Facts:

- Chestnuts were a staple food in parts of Europe.

- The American Chestnut was nearly wiped out by a fungal blight.

- Chestnut wood is rot-resistant and durable.

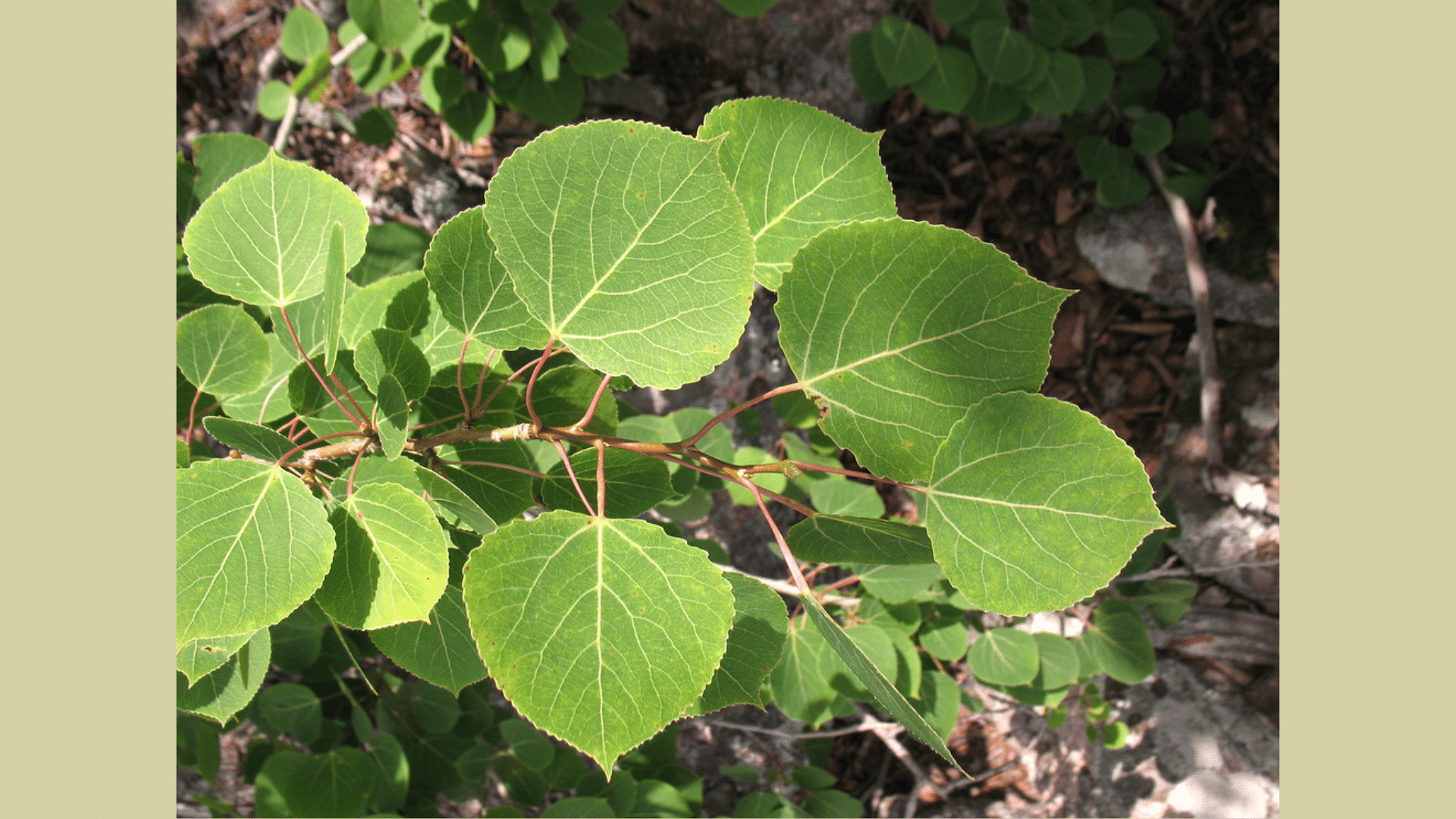

9. Aspen (Populus Tremula & Populus Tremuloides)

A type of poplar, aspens grow in groves and have fluttering leaves. They produce drooping catkins in early spring, with male and female flowers on separate trees.

Fun Facts:

- Aspen groves are often one organism, connected by roots.

- “Pando,” an aspen colony in Utah, is one of the world’s oldest living organisms.

- Their leaves flutter in the wind due to flattened stems.

How to Identify Catkins Easily

- Timing: Look for catkins primarily in spring, before full leaf development on many trees.

- Appearance: They typically appear as cylindrical, hanging structures, ranging from half an inch to several inches long.

- Color: Colors vary by species – silvery-gray (pussy willows), yellow-green (birch), reddish-brown (alder), or golden-yellow (hazel).

- Texture: Male catkins are often soft and flexible, while female catkins may be more rigid or cone-like.

- Location: They hang from branches, often more visible at the outer portions of the tree canopy.

- TreeSpecies: Identifying the tree itself is helpful – willows, birches, alders, and hazels are common catkin producers.

Some Interesting Facts About Catkins

- A single birch tree can produce up to 5 million catkins annually, each releasing thousands of pollen grains.

- Catkins provide critical early-season food for wildlife when other food sources remain scarce after winter.

- Some catkins, particularly from birch trees, are edible for humans and were used as survival food by northern indigenous peoples.

- Scientists use catkin emergence timing as a biological indicator in climate change studies due to its temperature-sensitive blooming patterns.

- Female willow catkins develop seeds with cottony attachments that can travel over 60 miles on air currents.

Wrapping It Up

Catkins represent one of nature’s most ingenious reproductive strategies, playing a crucial role in both tree life cycles and broader ecosystems.

These modest structures ensure the survival of willows, birches, and hazels while providing essential early-season nourishment for wildlife.

As spring approaches, watch for these formations in your local environment. Their appearance signals nature’s awakening and offers a perfect opportunity to connect with seasonal rhythms.

Notice their variety, from silvery pussy willows to dangling golden birch chains, each perfectly adapted to their species’ needs.